OUTDOOR RESIDENTIAL WATERING LIMITED TO ONE DAY A WEEK

TEN MINUTES per irrigation station

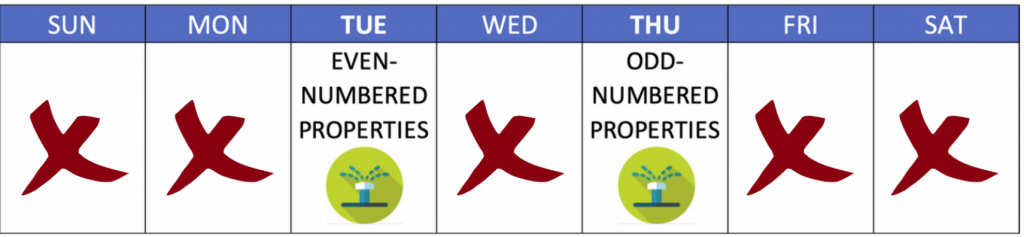

EVEN-NUMBERED PROPERTIES TUESDAY, ODD-NUMBERED THURSDAY

COMMERCIAL PROPERTIES PROHIBITED FROM IRRIGATING WITH POTABLE WATER

PER CALIFORNIA STATE EMERGENCY REGULATIONS

SEE DETAILS IN CAMROSA RESOLUTION 2022-08

- Trees and other permanent non-turf plantings for erosion control and fire protection are exempt from the one-day limitation.

- Drip systems, hand watering, and alternative irrigation are restricted to trees and permanent non-turf plantings.

- Pools/spas are not restricted by this declaration.

- Non-potable and recycled water is not affected by this restriction.

- Parks, schools, other spaces used for recreation, civic, and community events are exempt but expected to reduce 30 percent from 2020 use.

- Potable agricultural customers are likewise exempt, but asked to reduce 20 percent from 2020 use.

The rain and snow in December were not enough to fill regional storage and a web of state-level policies limits the amount of imported water that can flow out of the Delta. As a result, our imported water suppliers—the Department of Water Resources, Metropolitan Water District, and Calleguas Municipal Water District—do not have sufficient supplies to meet regular demands through the rest of the year.

In April, Metropolitan and Calleguas issued Emergency Water Conservation Programs requiring their retailers to go to one-day-a-week watering for potable outdoor irrigation on “non-essential” turf, which means homes and commercial, industrial, and institutional parcels.

On May 26, the Camrosa Board of Directors declared a Stage Two Water Supply Shortage, modifying the standard regulation in Camrosa’s Ordinance 40 to pass through the one-day-a-week outdoor watering limitation from our suppliers. Metropolitan deemed this level of response insufficient. In order to remain compliant and avoid fines from Metropolitan, on June 23, 2022, Camrosa moved to a Stage Three.

“Functional” turf—that is, ballfields, parks, and other spaces used for civic and community events—is exempt from the one-day limitation but such customers are expected to reduce 30 percent from 2020. Potable agricultural customers are likewise exempt, but asked to reduce 20 percent from 2020 numbers.

Camrosa recognizes the importance of the urban canopy and the utility of other non-turf permanent plantings in protecting against erosion and fire, and we encourage you to do what is required to keep that vegetation alive—while, as always, maximizing efficiency. Drip irrigation, hand watering, and other high-efficiency alternatives to spray irrigation for trees and other non-turf permanent plantings are encouraged.

HOA watering schedules should be determined by the customer address the HOA has on file with the District.

More information will be shared with customers in the coming days. This website will be your go-to place for all things drought-related as we head into another dry summer.